Installations

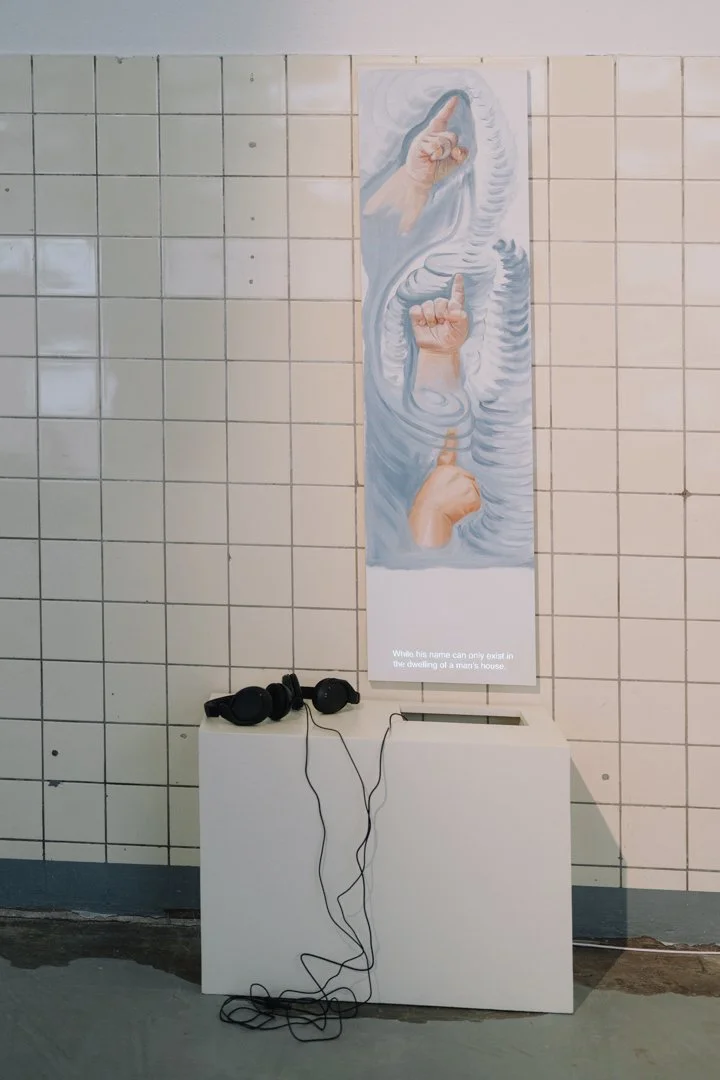

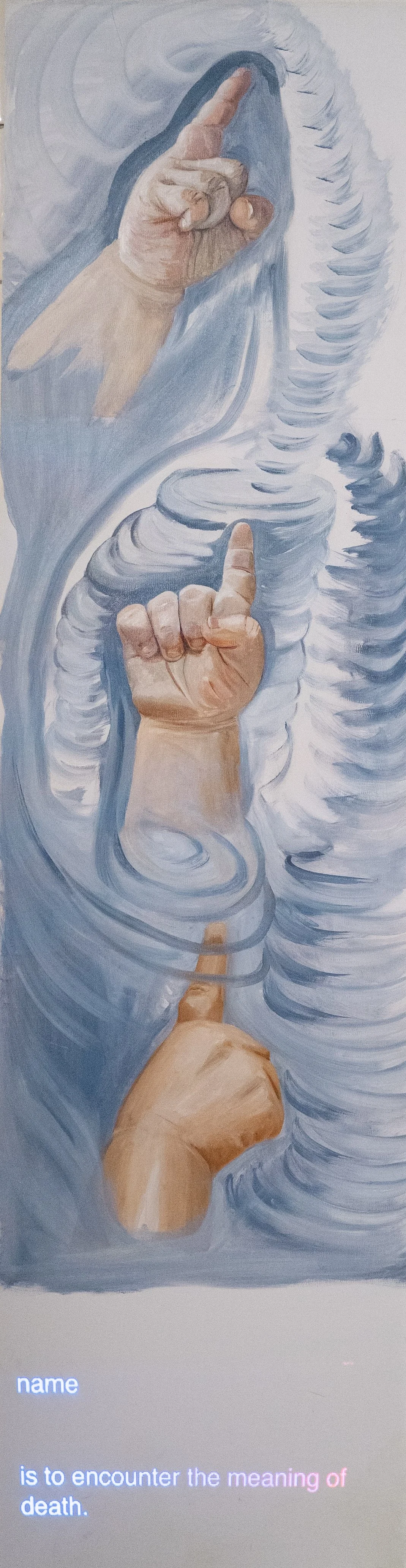

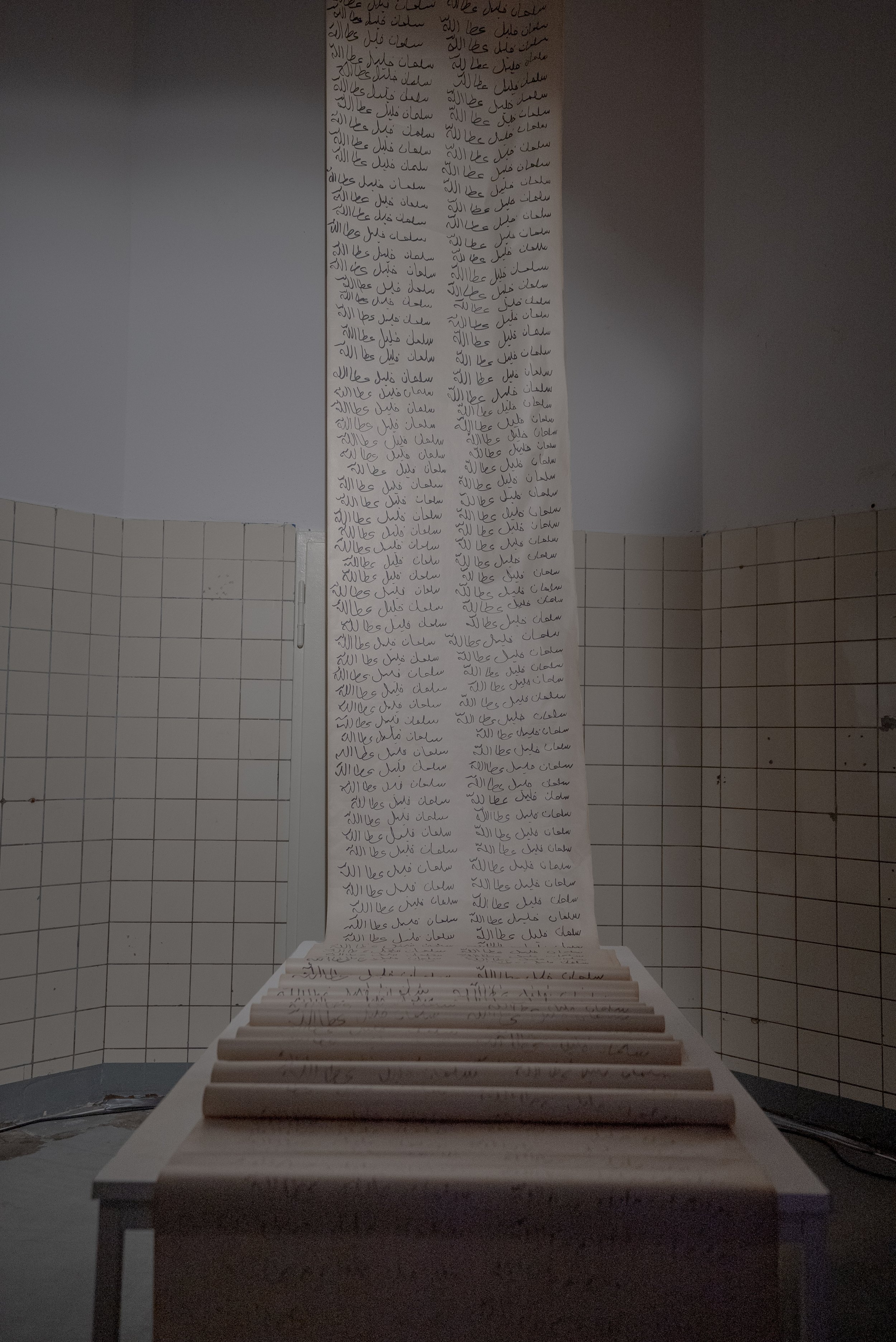

Name Me Not | Book of Names | Ashkal Alwan, moezeum | 2017-2025

‘Name Me Not | Book of Names’ stages the trajectory of a name, from a notion within the parents’ psyche (pre-birth), to a memory of a life once lived (post-death), passing through life’s labor in between. In his writings, Descartes believed that monkeys could potentially speak if they wanted to, yet avoid doing so in order not to be compelled into labor. To be named is to be addressed and identified, not only within families but most evidently by bureaucratic apparatuses.

Here, the governmental and the institutional journey of a name begins: from birth certificates to school records, from bank accounts to tax IDs, and from business cards to gravestones.

‘De-naming Salman Khalil Attallah’ attempts to stage the journey of a name fatigued by the bureaucratic repetition of its own inscription, until the ink of a pen –never used before– runs dry. Named after Lady Diana, the artist’s father was disappointed by her gender, which prevented him from naming her Saddam, after the Iraqi dictator he admired. In 2017, Diana Al-Halabi visited a hearing-impaired school in Beirut in search of a name that looks like her, rather than her parents’ political inclinations. She was given a sign name that resembles her curls. According to her, de-naming operates as a refusal against exploitative systems that cannot function without language.

Photo by Liza Wolters

THE POLITICS OF ARMED LIFEBOAT | Radius CCA | 2024

An exhibition hosted by Radius CCA Delft, showcasing the work of Diana Al-Halabi and Hilda Moucharrafieh, with a soundscape by Diane Mahin.

02.12.2023 – 11.2.2024

*The work produced for this exhibition is part of a longterm research “Famine and Hunger Strikes: Decolonizing the Digestive System” (2021-2024)

A note for the visitors of the exhibition by participating artists (Diana Al-Halabi - Hilda Moucharrafieh):

While we were preparing for this exhibition, we caught ourselves witnessing one of the biggest genocides Palestinians are undergoing by the Israeli Settler colonial state. The works in this exhibition have the taste of our attention dictated by the news we receive from our loved ones in Gaza. This is an interrupted exhibition, like every focus in the world must be interrupted because colonialism did not end. We stand by Palestine, and we call for you to learn its history under settler colonialism since 1948 up until our day.

“Record on the first page:

I do not hate people

nor do I encroach,

but if I become hungry

I will feast on the usurper's flesh!

Beware!

Beware my hunger

and my anger!”

Excerpt from “Record, I am an Arab!” - Mahmoud Darwish

My text for Radius publication:

When thinking of food, it is often the case to think about appetite, degree of physiological hunger, kitchens, and a choice of food that is affordable to eat. A constellation of the psychological, the physiological, and the economic. But is the political considered to be a part of this constellation?

Can we look through food, beyond the reductional micro of the biological, and towards a macro image of the political use of food? And arrive at the notion of political hunger, its precondition, and its aftermath. How can food be weaponized against people to subordinate them or ethnically cleanse them? How can famine inflicted by war, neo-colonial sanctions, or caused by climate change be a precondition to migration and thus affect its policy in Europe?

In my approach to the topic of political hunger, I have been working on the juxtaposition between famine and hunger strikes; one that comes from states, subordinating people in a top-down manner (famine), and another that uses hunger individually or collectively, but as a bottom-up resistance to fight for a right (hunger strikes).

In previous exhibitions, I used the concept of aprons made of mulberry fruit leather to speak about the question of preservation, food security, the domestic, the public, and the political. Who can preserve food beyond its season? Why preserve food? Is preservation a result of a surplus or a fear-taming method of protection?

Aprons, a domestic element used for protection against accidental stains, in this exhibition, mirror kinds of protection that surpass the domestic. What shapes does protection take when adopted by states and its apparatuses? Is it by creating borders? Migration policies? Systematic violence? Counterinsurgency techniques and ballistic shields?

This exhibition departs from these concepts and intersectionally relates the personal and the digestive to geo and necropolitics.

——————————————————————————————————————

A further take:

Schemes of isolating people like blockades, economic sanctions, border control, and apartheid lay in the very idea of isolating oneself in a safe space and the other in a precarious one, stamping it as a dangerous place. It is to elevate and gravitate oneself into the center of the world and the other into the periphery.

To do so, creating a “homeland” mirrors how life is percieved inside a home. A homeland is a land that needs to be marked as home, as a shelter, yet only for family members, while everyone else is a guest. In fortress Europe and its ongoing colonial artifacts such as the Israeli settler colony (a live example of the colonial past and its atrocities), I would rather call this isolation scheme an “insulation” scheme, from which this exhibition takes its inspiration.

According to Etymonline, the etymology of the word "insulate" is “the blocking from electricity or heat, state or action of being detached from others". The literal meaning is "act of making (land) into an island"; that of "a state of being an island."

Isolation and insulation work as two parallels, where the existence of one, by default, means the implication of the other. To isolate a nation is to build a wall around it, be it a physical wall, or be it by cutting electricity, water, internet, aid, or any economic exchange. We see this evident in Gaza, where the strip has been under siege for the last 16 years, and the Israeli settler colonial apartheid has been controlling the calories and liters of water that is allowed to enter. In October 2023, this siege had turned into a collective punishment, where having the upper hand to cut water on two million people is accompanied with internet blackouts to dim the ethnic cleansing happening.

To that end, when we speak of apartheid, it is vital to remember that insulation takes place when the extraction is manipulated and incorporated inside the aforementioned “home.” A glass reflective foil is then necessary to make unclear what has been extracted and hidden behind walls and to enter a process of gaslighting and victim blaming those who come to ask for their stolen rights.

This exhibition is about who owns the means of power, and how the domestic is a model for fascist politics to take control of the bodily, the visceral, and the digestive of the people and use it as a means of subordination.

No one is safe except those who know how to navigate the hell they created. Those who live not in bunkers but own them, those who know how to keep their emergency-alert sirens in check. Reminding their people that the danger is not only a tale of the past but also lives in the present, even if imaginary, and in the near future, eventhough as a possibility. Those for whom the machine that creates sanctions, arms, and the graphs for a free economy is the machine that protects them from those who are crawling to their shores.

“To protect” oneself – a canon used in rightwing fascist discourse– is to work towards a condition of being unaffected by and indifferent to the political climate.

Oftentimes, the term “protecting oneself” is dropped, and the term “defending oneself” is delusionally adopted. “To protect” is to assess the foreseen dangers and take preventive measures, but to defend oneself surely should mean that an attack has already happened and it is time to defend oneself. In both cases, the entity of danger is often imaginary, created to imply fear of that which is the other, and in better words, it is a method of prioritizing a life over the other. A tool that allows a cold war to be inherited from one generation to the other. A method of regenerating a sense of superiority bound with fear to keep a position of power.

“In the state of siege, time becomes space

Transfixed in its eternity

In the state of siege, space becomes time

That has missed its yesterday and its tomorrow.”

Excerpt from “Gaza’s Siege” - Mahmoud Darwish

CHEWING WITH POLITICAL TEETH | Garage Rotterdam | 2024

Constituting two sides of the same coin, famine and hunger strikes render the digestive system another political site of struggle. While famines are a top-down force often engineered by governments to subordinate their people, hunger strikes are a bottom-up form of individual resistance often undertaken by political prisoners as a last resort for claiming their rights.

The Digestive is Political

"Chewing with Political Teeth" , Fruit leather aprons - installation view at Garage Rotterdam | Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

The question of preservation is foregrounded in this piece, feeding into the notion of food security, the domestic, the public, and the political. Who is able to preserve food beyond its season? Why do we preserve food? Is preservation a result of surplus or is preservation a fear-taming method?

Informed by Lebanon's long-standing practice of mulberry farming, this piece uses mulberry fruit leather as a means of memorializing the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon. Prior to the famine (1915-1918), mulberry trees covered 80% of Mount Lebanon’s terraces, which resulted in the emergence of monoculture silk farming and the accumulation of increasing debt on the part of peasants seeking to keep up with the capitalist trade of silk in Europe, particularly in France. Due to the lack of cultivation of other crops (e.g. lentils and burghul), the blockade imposed by Allied forces during WWI resulted in a famine that killed more than 200,000 people. For the next twenty years, post-famine Lebanon was placed under the French Mandate.

"Chewing with Political Teeth" , Fruit leather aprons - installation view at Garage Rotterdam | Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

Criticizing the omnipresent notion in the West that famines are a thing of the past, this project provides a visual translation of the direct and indirect relationship between politics and war, on the one hand, and the digestive system, on the other. With the ongoing famine in Yemen (circa 2016), increasing effects of climate change, a neocolonial strategy of sanctions whose only victims are peoples (instead of governments) across the Global South, and the current outcome of Russia’s war against Ukraine (inflation and insufficient global supply of wheat in particular) we are witnessing the crucial role that food security will play in both the present and the future.

THE OFFICIAL APOLOGY OF HOGESCHOOL ROTTERDAM | 2021

A wall text, vinyl cut-out letters on white wood. 210x180cm

After censoring students for being vocal about their stance in solidarity with Palestine, this work imagines an alternative reality of the Hogeschool Rotterdam response. A curatorial text hijacked and written by Diana Al-Halabi at the graduation of MFA at Piet Zwart Institute

The Text:

Material Contexts

Graduation Show 2020-2021

Text by Hogeschool Rotterdam/WDKA/PZI

While our educational team and curators were in the process of putting together this graduation show of the MFA students at Piet Zwart Institute, our students in the Karel Doormanhof building were trying to protest a cause as crucial as life itself. We responded “We see you, we hear you” while we were in fact practicing surveillance as we acted blind.

The modes of response we adopted were undoubtedly bureaucratic and at times were identical to state policing. Under the guise of a care economy, we forcibly confiscated banners, censored students, invited them to Kafkaesque meeting conditions. We covertly assumed that time will tire everyone, demands will naturally die off, and we’ll eventually get back to normal.

While trying to preserve our “white innocence” as Gloria Wekker puts it, we failed to embody the token we claim to represent. We claimed to be inclusive while we were in reality only tolerant, and to be tolerant is to endure, however, endurance was never a synonym for inclusivity.

In the past month, we have learned from our students that change comes if we learn how to employ our privileges to help those who are oppressed and marginalized. Therefore, allow us to use this graduation show as a platform to voice a public apology to our students for censoring them, to our tutors for making them doubt their role in teaching decolonial theory.

And to Palestinian people all over the world, we say, forgive us, we are late.

Hence, we announce our endorsement of the “Palestine Solidarity Statement” written by the Graduate Gender Programme at Utrecht University. We commit from this day forth, to be anti-colonial in practice and management as much as in theory, and to push higher authorities to endorse a BDS policy. We wish our students a graduation full of pride, and a future full of change.

THE VISA REGIME BANNER

Ink on an outdoor banner, a collaboration with Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

(part of open studios at PZI) | 2021

The banner “If a curfew violates freedom of movement, so does the visa regime.” placed on the emergency exit of Piet Zwart Institute, is a protest against the silence of European authorities towards the long-lasting curfew so-called the visa regime. This statement is a response to the current events taking place in the Netherlands and beyond, where a male-dominant discourse is critiquing the temporary curfew as a “violation of freedom of movement”.

If violated, what different meanings could “freedom of movement” have depending on whose mobility is affected? This question was the point of departure of this project. In the current Covid-19 pandemic, the government of the Netherlands has taken different measures to limit the spread of the Coronavirus. One of them is a curfew. When implemented, riots stormed the streets for a few nights. The debate went into court and initially, the Hague District Court called the curfew a “far-reaching violation of the right to freedom of movement and privacy”.

Only a few, mostly right-wing groups in the Netherlands, have addressed their opposition to the curfew as a violation of freedom of movement. Those are the same groups that usually push nationalistic agendas, reinforce strict Schengen visa regulations, and vote against facilitating easy access to migrants and refugees fleeing war and economic hardships.

The double standard of what freedom of movement means, makes us intrigued to ask, what does the European border regime do to freedom of movement when it fortifies its borders and treats newcomers as the “other” who is only welcomed if it serves as a commodity in a capitalistic society?

Diana Al-Halabi and Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

YOUR GUIDE TO TAKING BACK (TEMPORARILY) WHAT WE HAVE TAKEN FROM YOU (PERMANENTLY) | 2021

digital downloadable work | (part of Print& Play exhibition - Boijmans Museum) | 2021

In the age of “total bureaucratization,” a term coined by David Graeber, the mobility of people is tied to bureaucratic requirements and policies drafted precisely to limit and slow down freedom of movement. In this artwork, I use the image of Dutch right-wing anti-immigrant politician Geert Wilders within the format of a visa headshot specification, a document usually found on immigration websites. To place the face of the most xenophobic politician onto exemplary bureaucratic templates underscores the satirical thrust of the project, while exposing both the banality and the violence embedded in such requirements.